When I was at the Willamette Writers Conference this year, I coached several writers after reading samples of their work as part of the manuscript critique service that the conference offered.

When I was at the Willamette Writers Conference this year, I coached several writers after reading samples of their work as part of the manuscript critique service that the conference offered.

What I found was that almost every writer I sat down with could benefit from exercises in finding a strong and appropriate storyteller’s voice.

You might think that a strong storyteller’s voice is only important for fiction or narrative nonfiction writers, but that’s stinkin’ thinkin’, my dear writer.

Writers in every genre need a strong storyteller’s voice. Any kind of story without a strong storytelling voice is not worth the time of the readers, and the time of readers is the primary concern of writers of all stripes today.

Even book jacket copy merits a strong storyteller’s voice. Without it why should anyone spend money and commit the time necessary to reading an entire novel?

So, if you are not sure if you have a strong storyteller’s voice, then you need to find out if you do or not. And if you don’t, then this is a skill you need to work on. After all, your story and your readers are depending on you to have one. A writer is a storyteller first and foremost. There is no wiggling off the storytelling hook.

In her website bio, DiCamillo says, " I write for both children and adults and I like to think of myself as a storyteller."

But, please, do not make the mistake of thinking that a writer’s job is to come up with one trademark voice and serve that voice throughout a career. That’s just ego talking. Beware of branding experts in this regard. That is not the kind of advice that is going to serve your writing career in the short run or the long run.

Every story, indeed every single thing you write, deserves its own, unique storytelling voice. It’s your job as the writer to pay attention to what the storytelling voice wants to be and then serve that voice.

For any writer seeking to understand and then strengthen the storytelling voice, I have a book recommendation. I do not think that you can read this book and not understand the important melding of storytelling and voice to create a unique storytelling voice that brings readers clamoring back for more.

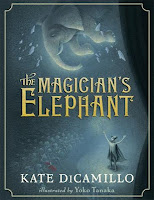

The book is The Magician’s Elephant by Kate DiCamillo. Kate DiCamillo is an award-winning author and for good reason. She also wrote Because of Winn Dixie and The Tale of Despereaux.

Once you read The Magician’s Elephant you will understand storytelling voice without question. And I don’t think you will ever forget it. And if you are still fuzzy on it afterwards, this is a short book that can be read over and over until you absolutely get the idea that each and every piece of writing comes part and parcel with a unique storyteller’s voice.

Could this book have been told in any other voice? Nope. That’s because The Magician’s Elephant has a unique storyteller’s voice. DiCamillo found it and served it. And the result is an outstanding, timeless read.

And isn’t that all any of us want to hear about our books?

Then, your job, my dear writer, becomes to find the just-right storyteller’s voice for every single one of your projects. And this takes time and patience and skill.

Start by understanding what you are looking for. Start by learning the importance of storyteller’s voice.

Here are the opening lines of The Magician’s Elephant:

At the end of the century before last, in the market square of the city of Baltese, there stood a boy with a hat on his head and a coin in his hand. The boy’s name was Peter Augustus Duchene, and the coin that he held did not belong to him but was instead the property of his guardian, an old soldier named Vilna Lutz, who had sent the boy to the market for fish and bread.

That day in the market square, in the midst of the entirely unremarkable and absolutely ordinary stalls of the fishmongers and cloth merchants and bakers and silversmiths, there had appeared, without warning or fanfare, the red tent of a fortuneteller. Attached to the fortuneteller’s tent was a piece of paper, and penned upon the paper in a cramped and unapologetic hand were these words: The most profound and difficult questions that could possibly be posed by the human mind or heart will be answered within for the price of one florit.

Peter read the small sign once, and then again. The audacity of the words, their dizzying promise, made it difficult, suddenly, for him to breathe. He looked down at the coin, the single florit, in his hand.

“But I cannot do it,” he said to himself.

Comments on this entry are closed.

Christina, I appreciate this reminder of how finding our own “unique storytelling voice” is the key ingredient needed to engage our readers. It seems so simple and yet it really does take time, patience and lots of writing to discover. Kate DiCamillo’s excerpt brings it home nicely. Thanks for sharing!

Oh, I agree.

Kate DiCamillo’s excerpt brings it home nicely.